The Functions of Cinema

Chapter 1

Cinema is the most complex, collaborative and prestigious art-form. It is the artform with the greatest impact, the biggest budgets and the most widespread audiences. 246 million people of the US/Canada population attended the cinema at least once in 2016( MPAA, 2016 ). Given its prevalence in modern human culture, it would be beneficial to ask what films are really for, what purpose it serves, and what films can do for us. Being able to understand the functions of cinema could assist us in picking, amongst the huge variety of films made and to be, the films that most interest us and benefit us emotionally and intellectually. The films that can benefit our lives in a profound way. So what are the functions, if any, of cinema? In this essay I will pursue to outline its functions and roles in our society, which are numerous and often overlap, for example, making the audience laugh at a comedy or cry at a drama can both be considered as therapeutic functions. So, I will categorize film’s many functions into three main functions that are its functions of therapy, information/education and of influencing attitudes.

The famous french advertising slogan that says, “When you love life, you go to the movies,” it’s false! It’s exactly the opposite: when you don’t love life, or when life doesn’t give you satisfaction, you go to the movies.” ― François Truffaut

The quote by the french director and one of the leading figures of the French New Wave, expresses how he concieved of cinema, as a kind of therapy. This idea isn’t new, during the 5th century B.C.E.,when cinema’s predecessor, theatre, was a flourishing and significant cultural activity in Ancient Greece, the classical Greek writers thought that facing tragedy was a healthy and necessary antidote to human foolishness(Wheeler, 2015). Aristotle, who concluded that a good tragedy could, through letting us witness the downfall of a good character by consequence of his or her hamartia, or tragic flaw, induce fear and pity in the audience, which leads to catharsis, a release of these emotions, inspiring us to be more sympathetic and forgiving towards others and ourselves.

“Tragedy is more important than love. Out of all human events, it is tragedy alone that brings people out of their own petty desires and into awareness of other humans’ suffering. Tragedy occurs in human lives so that we will learn to reach out and comfort others” -C. S. Lewis A study in 2005 by S C Noah Uhrig of the University of Essex entitled, “Cinema is Good for You: The Effects of Cinema Attendance on Self-Reported Anxiety or Depression and Happiness” the author describes how attending the cinema can have independent and potent effects on psychological well-being because audiovisual stimulation invokes a variety of emotions, and the cumulative experience of these emotions through films provides a safe backdrop in which to experience roles and emotions we might not otherwise be able to experience. The Ex. Chairman of the BFI and accomplished film director Anthony Minghella states “…Fiction becomes this sort of cultural bank balance that we can draw from. We can momentarily be a young woman, an old woman, a black person, an Asian person, a Chinese person, and look at the world and argue a position that is not our own for a while—inhabit a position that is not our own.”

Today we have Cinema therapy. Cinema therapy is defined by Segen’s Medical Dictionary as:

“A form of therapy or self-help that uses movies, particularly videos, as therapeutic tools. Cinema therapy can be a catalyst for healing and growth for those who are open to learning how movies affect people and to watching certain films with conscious awareness. Cinema therapy allows one to use the effect of imagery, plot, music, etc. in films on the psyche for insight, inspiration, emotional release or relief and natural change. Used as part of psychotherapy, cinema therapy is an innovative method based on traditional therapeutic principles.”

Programs such as MediCinema places cinemas in hospitals and screens films for patients, have provided vital support for over 17,000 patients and families in 2015 (Medicinema, 2015). Author of The Motion Picture Prescription and Reel Therapy, PhD, MPH, MSW, Gary Solomon, states that that viewing television or film movies “can have a positive effect on most people except those suffering from psychotic disorders.” The Chicago Institute for the Moving Image (CIMI) supports people seeking therapy for serious psychiatric illnesses such as depression schizophrenia or amnesia, to essentially create their own films.

“We work with patients who tend to have personal interests in making a movie or a screenplay and are already working with a therapist,” says Joshua Flanders, CIMI’s executive director.

Next is cinema’s role of influencing attitudes and incentives. A newborn has no particular attitudes toward war or marriage, but through a variety of sources, he/she will acquire them in time. One of these sources may be film, because the capacity of cinema to help create and modify attitudes and incentives seems to be well established. (Mercer 1953) In new research, Michelle C. Pautz examined the impact of two recent movies namely Argo and Zero Dark Thirty, on viewer’s perceptions of government. She has found that after seeing the two films, many of the participants’ opinions changed, with the majority expressing higher degrees of trust in government and adopting a more positive perception of government performance(Pautz, 2014).

A study conducted in 1995 by Stanford University psychologist Lisa Butler and her colleagues of viewers before and after seeing the controversial conspiracy film JFK(1991), discovered that watching the film “doubled the level of anger” of viewers. (BUTLER L. D. ; KOOPMAN C. ; ZIMBARDO P. G., 1995). Additionally, it also seems to have impacted their political intentions. Seeing the film “was associated with a significant decrease in viewers’ reported intentions to vote or make political contributions.” (BUTLER L. D. ; KOOPMAN C. ; ZIMBARDO P. G., 1995). The authors attributed this reaction to a “general helplessness effect” generated by seeing the film. The vast conspiracy proposed by the filmmakers made people feel powerless.

Of course, film’s capability of shaping perceptions of its viewers can also work for the wrong ideas. Perhaps the most significant example of cinema’s effects on a mass public is demonstrated in films such as the Nazi documentary Triumph of the Will(1935) directed by Leni Riefenstahl. In his brief preface to Hinter den Kulissen, Hitler describes Triumph of the Will as “a totally unique and incomparable glorification of the power and beauty of our movement.” American film critic and historian Roger Ebert states that Triumph of the Will is “by general consent [one] of the best documentaries ever made”, while american writer and filmmaker Susan Sontag considers the film to be the “most successful, most purely propagandistic film ever made”. Another example is D.W. Griffith’s inflammatory silent epic The Birth of a Nation(1915). The Birth of a Nation whose portrayal of the Ku Klux Klan as a heroic force was considered a catalyst for gangs of whites to attack blacks.

“Of all of our inventions for mass communication” said Walt Disney “…pictures still speak the most universally understood language.”

The quote above illustrates cinema’s potent and far-reaching ability to educate. Cinema allows us to discover the unknown (Mercer, 1953). Themes explored in film expresses itself in a form that anyone is able to comprehend and appreciate regardless of background, education or race, which makes it a truly democratic artform. (Solomons, 2011) We are able to observe cultural differences and engage with all sorts of diverse attitudes and approaches to life when we extend our viewing horizons beyond what we are used to and the mainstream. (Solomons, 2011)

“Movies have become a world-wide feature and as it relates to what movies tell us? I don’t know that I knew as much about, for example, Cuba as I wanted to – I’m talking socially not politically. We (the Academy) sent an outreach program to Cuba, and we learnt so much about the society from their movies. I believe, personally, that movies allow people to be taken places they can’t get to on their own- be it travel, or culture, or learning.” -Tom Sherak, President of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences

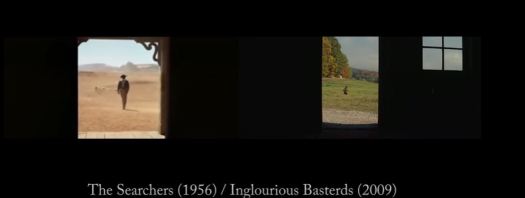

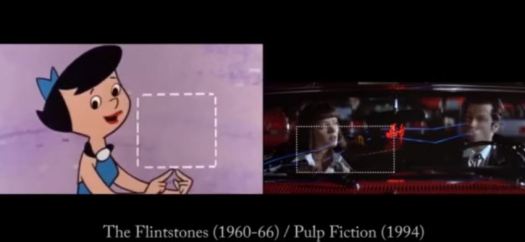

By seeing films from different parts of the world, we are given a window into people’s differences and similarities. In this way we can each develop a better understanding of ‘the other’: an understanding that avoids stereotypes and acknowledges both the unity and diversity in humanity. (Yazdani, 2005)

For Dr. Pautz, movies “can be a great mechanism for conversation and reflection.” They can also “help us understand societal opinions, help us understand institutions, and even demystify aspects of society.” A film like “Selma” or “American Sniper” can be a “wonderful mechanism for discussing highly charged topics in society, and providing a way to tackle issues without doing it outright.” She added, “Discussing race relations/racism is still hard for Americans and an often taboo subject, but one can much more easily talk about a movie that might then lead to conversation about those more sensitive topics.” Movies contribute to the “political socialization of people (young adults in particular),” Dr. Pautz said, “and so what audiences watch and how certain institutions are portrayed over time can be very significant.”

Increasingly, historians have begun to not only document a history that chronicles wars, treaties, and presidential elections to one that tries to provide an image of the daily life of the people: how they worked, what they did for fun, how families were formed or fell apart, or how the fabric of daily life was formed or transformed. Social history developed from marginal and tentative origins at the end of the nineteenth and the beginning of the twentieth centuries and experienced a triumphant expansion from the 1950s to the 1980s.(Conrad, 2001) Film has an important role to play in these histories. Movies may offer the best evidence of what it was like to walk along the streets of Paris in the 1890s, what a Japanese tea ceremony was like in the 16th century, or how people worked in factories or spent a Saturday morning in the park. Undoubtedly, these affairs could be staged and distorted, but as a record of time and motion, films preserve gestures, gaits, rhythms, attitudes, and interactions in a variety of situations. From the way a Buddhist monk in Ceylon folded his robe in 1910 to the way passengers alighted trolley cars in San Francisco in 1925, one can witness these activities in motion pictures.

Our horrified awareness of the Holocaust relies partially on the filmed images of the Nazi concentration camps, and our consciousness of the disaster of the atomic bomb stems partially from images of Hiroshima at the end of the second world war. On the other hand, twentieth-century devastations or traumas that went undocumented by film – such as the Armenian genocide or the Great Chinese Famine – are less prevalent in public consciousness because of the lack of vivid images. ()

Of course, because the vast majority motion pictures are fictional, we must evaluate the validity of fictional films as pieces of historical evidence. Fictional films serve as historical evidence in the same way other representational artforms do – by making events lucid, describing social attitudes, and even exposing the unconscious beliefs of past societies. Griffith’s The Birth of a Nation cannot be viewed as an objective or accurate portrayal of the era of Reconstruction, but it does – agonizingly, and even unpurposefully – express the kinds of hysterical anxieties and cruel fantasies that underlay American racism, particularly in the beginning of the twentieth century. Attitudes about gender, class, and race, as well as heroism, work, and love are all reflected in fictional films as they are in an era’s books, plays, and paintings.

Like all art, cinema is essentially a form of expression and hence, communication. Communicating stories, ideas, emotions and experiences, it is a form of therapy, as well as a form of education and inspiration. Cinema is a relatively new, rapidly developing and extremely complex art form, that finds its place in many people’s lives the world over.

Chapter 2

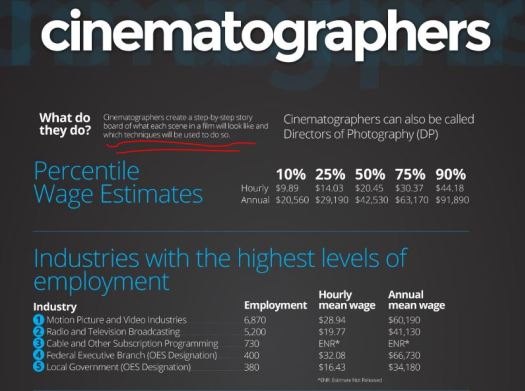

I will talk about 2 examples of film that has well served the functions of cinema that I have outlined, which are the functions of therapy, of education and of influencing attitudes. The first film is The Last Emperor(1987) directed by Bernardo Bertolucci, which won 9 Oscar awards for best picture, best cinematography, best costume design and so on. “Remember puyi? Probably not. So let The Last Emperor illuminate and enchant you with an unforgettable history lesson” states noted film critic Bruce Williamson in his review of the Chinese biographical epic that tells the story of Pu Yi, the final emperor of China, who became a god at the age of three, and a his final years, a humble part-time gardener. The makers of the film deserve to be applauded and admired for bringing from an eastern culture, the tale of Pu yi – a largely unknown historical figure – into the attention of the Western audience( Lu, 1994 ). Film critic and historian Roger Ebert’s comment noting the awe-inspiring presence of the Forbidden City, authentic wardrobe and thousands of extras to recreate the everyday reality of the wistful little boy, makes for a vivid and highly informative journey to another world of a subject as “remote and untouchable”( Mcarthy, 1987 ) as the last imperial ruler of China.

One of the most poignant and tragic scenes in the motion picture, when a bicycle is gifted to the teenage emperor who immediately pedals it around the Forbidden City enthusiastically until he comes to its gates to the outside world, and is barred by his own guards – He is an emperor who cannot do the one thing any other boy in China could do, which is to go out of his own house -. (Ebert, 1987).

Having a passionate interest in documentary photos and film, it is clear why I have chosen this film as an example. For bringing light to the story of the “largely unknown historical figure” that is the last emperor of China, by following the life of Pu Yi himself, informs us about the true reality of his ironically imprisoning life as emperor, as his biographer Edward Behr remarked, “his palace was the first of his many prisons”. It also educates us, with vivid and historically realistic images, about the extremely volatile and significant period of early 20th century in China, which underwent some of the biggest changes in Chinese history. As a form of art it fulfills its function of therapy by putting in front of us, the tragic tale of the wistful boy, who threw his pet mouse, his only friend at the age(***), out of anger, at the gates that barred his freedom from the palace.

Created before the first image of the full view of Earth from space was available, 2001: A Space Odyssey took us on a cosmic voyage – beginning in the African deserts on Earth millions of years ago, then out into the galaxy, to the moon and Jupiter. – with one of the most sublime, inventive and awe-inspiring artistic works of the 20th century. The film was deemed “culturally, historically, and aesthetically significant” by the United States Library of Congress in 1991 for its undisputed and far-reaching influence. Upon release, the film polarized critical and public opinion – some critics called it “too boring”(Alder, 1968), or that it “lacks dramatic appeal”(Robe, 1968), “too abstract”(Sarris, 1968) or “a film out of control”(Schlesinger, 1968), while others considered it “a milestone, a landmark for a spacemark, in the art of film”(Champlin, 1968), or that it “succeeds magnificently on a cosmic scale”(Ebert, 1968). But unchallenged is the acclaim and admiration for 2001’s scientific realism, visual inventiveness and accurate futurism. Labelled as “perhaps the most thoroughly and accurately researched film in screen history with respect to aerospace engineering” by four NASA scientists, who based their nuclear-propulsion design partially on the movie’s “Discovery One” spacecraft, the 1968 film set a “hugely inspirational”(Lucas****) and impressive example that was way ahead of its time. Director Ridley Scott stated he believed 2001 was the “unbeatable film that in a sense killed the science fiction genre”. Steven Spielberg claimed it was his film generation’s “Big Bang”.

Perhaps the most profound moment in the film, and in my opinion one of the most poignant moments of all cinema, came with the two words – “I’m afraid”. When HAL, the artificial intelligence of the spacecraft’s onboard computer, the brain of the ship, turns against the humans of the mission and kills all but one of them, the surviving member Dave Bowman manages to manually re-enter the spacecraft after being locked out by HAL, and goes to deactivate HAL. Keeping in mind that earlier in the film, the humans admits that they “don’t think anyone can truthfully answer” whether or not HAL can have genuine emotions, as Bowman proceeds to HAL’s processor core, HAL attempts to console Bowman with “I know everything hasn’t been quite right with me, but I can assure you now, very confidently, that it’s going to be alright again.”, and when ignored, he pleads “Dave, stop. Will you?”.Still disregarded, and as Bowman begins to gradually disconnect the circuits of HAL’s core, we hear “I’m afraid”, “Dave, my mind is going, I can feel it”, and finally spending the last moments of his “life” singing “Daisy”. Ironically, HAL is the character that expresses the most feeling in the entire film, and his unexpected “artificial” appreciation of “life” makes his death one of the most profound tragedies of art. Literature and film critic and poet Dan Schneider stated that 2001: A Space Odyssey has “one of the greatest screenplays ever penned”, writing “I recall the HAL ‘death scene’ as one of the few filmic moments to ever cause me to tear up in sadness”.

I chose 2001: A Space Odyssey as my second example for many reasons. Firstly, it was a film that explored many subjects that interest me greatly, such as space exploration, human evolution, artificial intelligence and artificial consciousness. The film was an intellectual project as well as a piece of art, created out of meticulous research combined with Kubrick’s grand cinematic vision and brave imagination, which inspires me greatly as it sets itself as an example of the type of film I hope to make, one that reflects the potential of human intelligence and imagination, and also invokes a release of emotions through the depiction of a tragedy. Furthermore, it raised the bar of cinema, particularly science fiction cinema and inflamed the public’s curiosity of space exploration.

Chapter 3

I am making a narrative short film with the hopes that it should perform the functions of film that I have mentioned. Ideally, my film would –

- serve as a form of therapy ; Through audio-visual stimulation my audience should experience catharsis after conceiving the tragedy of the protagonist’s downfall at best, or at least provide the audience an escape from their concerns for the length of the film.

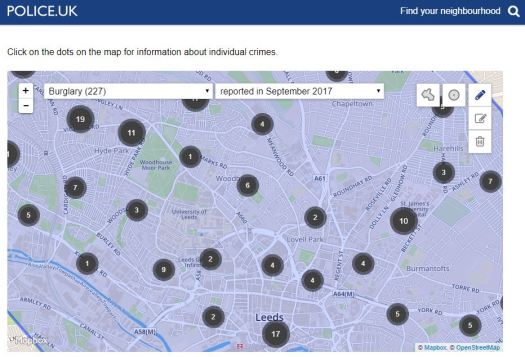

- It would inform audiences of the pervasiveness of burglary in Leeds, and of how vulnerable houses are

- It would also persuade the audience of the harsh reality of leading an unlawful life.

I wanted to create a cold, dark and harsh world for the lead characters, who are criminals, to inhabit. Psychologically, it should stimulate a mysterious, unnerving, sinister awareness. Many changes and developments were done towards this ambition.

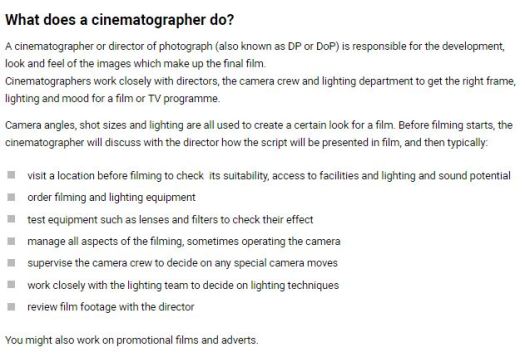

In terms of cinematography, I decided, in the end, to cut out any scenes that were shot in day time, so all of the film would be set at night, to endorse the aforementioned intended effect. We also reshot the scene of Harry singing in his room. I wanted it so that even the “happiest” moments of our protagonist, those of which were spent with the girl, are set in harsh and uncomfortable environments – chatting outdoors in strong winds, and in rain, upon concrete, in lifeless and remote locations, almost always stood up – , to endorse the unceasingly harsh reality of protagonist’s criminal way of life, never allowing them to feel fully “comfortable” and happy. In order to create a more shocking effect upon our protagonists death, I decided to discard all scenes of “the house resident/attacker” prior to the scene of him striking the protagonist, because having those scenes would indicate danger before danger happens so his death is less shocking. Although here I realize I am choosing between suspense or surprise – if I show scenes of “the attacker” in the house, it would be suspenseful to watch the burglar protagonist, who unknown to anyone’s presence in the house, slowly looks through the room.

Initially planning to focus on realism when it comes to lighting, I decided to light the interior of the house, the location of Zen’s death, with a strong red and blue to create a sort of fairy tale appearance, even though after shooting I still felt hesitant due to the bizarreness of a house lit in bright red, worrying that the audience would not buy it, I decided in the end to continue with it firstly because of aesthetic reasons – it looked a more interesting and appealing compared to the colors that would represent a normal empty house at night- and secondly because the red was a good stimulant and pulse raiser to give an impression of danger, aggression and death, and the blue gave an eerie and melancholy feel to the scenes.

In terms of editing, one element of film I have planned to use frequently in this film is the flashback element. Initially editing according to music or attention holding timing, I decided that the flashback scenes work much better and more convincingly if they are put in when the actors appear to look like they are actually thinking, for example, looking down, or shutting their eyes, or gazing blankly at something, so I changed the edit to suit this discovery. After receiving frequent feedback on the film’s confusion, I decided to repeat short clip of the scene of Harry walking away after having taken revenge and killed the house owner who killed Zen, and freeze-frame with the dead victim in the background – a technique frequently used by Martin Scorsese – in order to aid the comprehension of the film by reminding the audience the earlier incident and resolving the mystery introduced at the start.

Initially I had planned that the protagonist should win the brawl against the attacker and survive, even after what seemed to be a deadly strike on the temple of the protagonist, but after filming and reviewing it with a few friends of mine, we decided it was more tragic that he should not survive, and not be able to escape to Malaysia – the girl’s home country, which she reminisces about in the end of the film – with the girl, so I discarded the scene that shows he survived the fight (Fig ***). The fact that the protagonist has been portrayed so far as a skilled, agile, fearless criminal, makes the sudden and shortlived confrontation more tragic.

In terms of sound, I had initially planned to have a music score accompanying the entire burglary scene from his entry into the until his death scene. Harry had already made a score for it called “Knockout”, but we decided to drop all music once he entered the room, so all we hear is the protagonist’s careful footsteps and rummaging made loud by the contrast of the quiet ambient noise of the room. The music would have aroused tension and expectation, without it, his search through the room is more suspenseful and unnerving, and the revelation of the crisis revealed by the watch’s reflection, is made more shocking and thrilling. We had initially planned for Harry to sing “Bring It On Home To Me” by Sam Cooke, but in the end I felt that it did not tragic enough for the film, and also because I felt the song did not use the best of Harry’s voice and style. So to have a song more suited to him, we decided to have him sing his own original music, which is the song used in the film.

vc

vc